PFAS in landfill leachate: Why 2026 turns your residual chain into an operational bottleneck

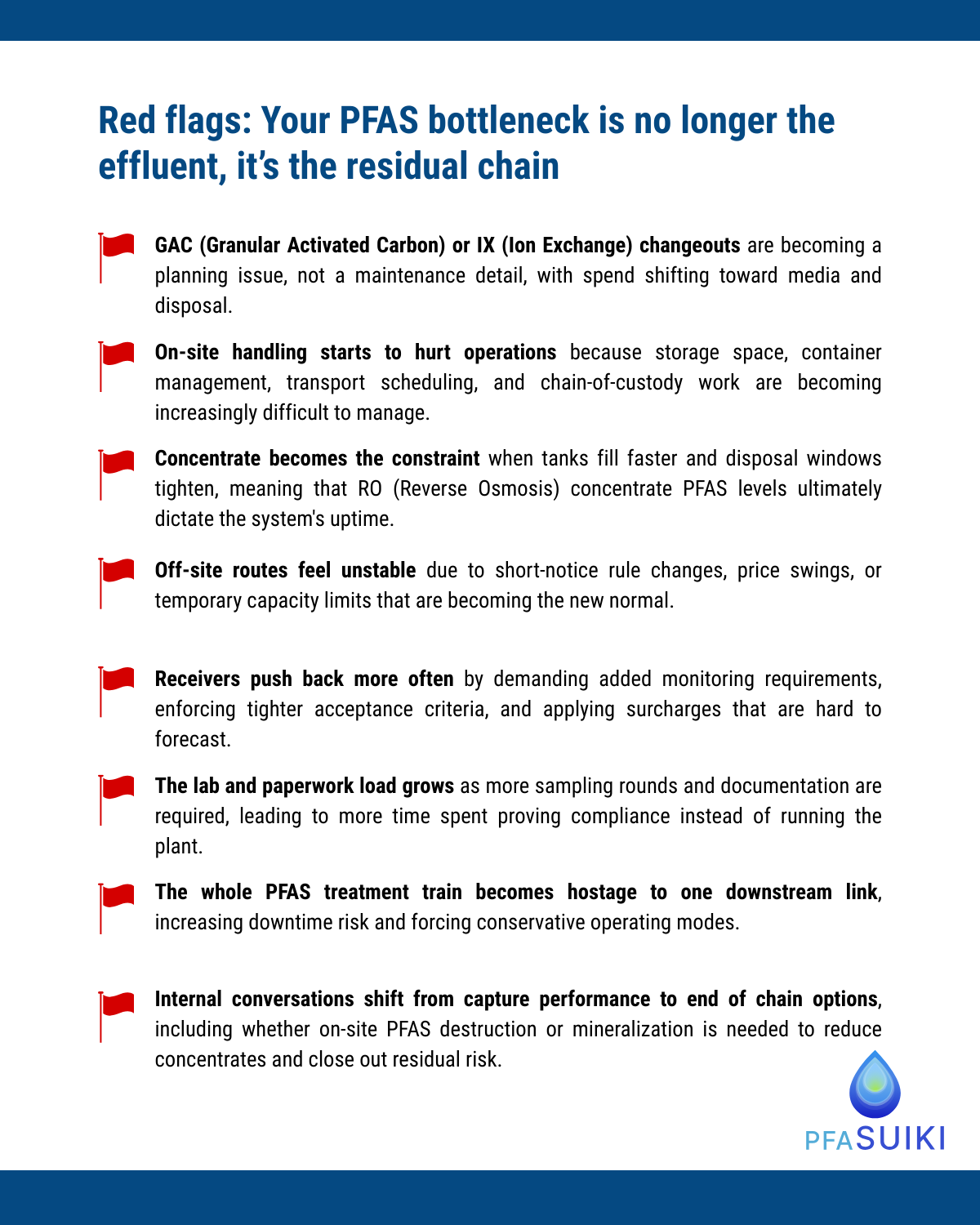

Effluent numbers may improve, yet operations are becoming increasingly fragile. With the EU’s 2026 PFAS requirements now in full effect, regulatory and public pressure is moving upstream. The critical bottleneck is no longer just the treatment process itself, but the residual chain: spent media, concentrates, off-site acceptance, and the liability trail created by every handoff.

The shift from future risk to operational reality. PFAS is no longer a future compliance topic. In the EU, updated PFAS requirements under the recast Drinking Water Directive (DWD) entered into application in January 2026, alongside harmonized monitoring and reporting expectations across Member States.

While the legal scope targets drinking water, the operational impact extends beyond water utilities. As PFAS is measured and compared more consistently at the endpoint of the water cycle, scrutiny shifts upstream toward sources, transfers, and side streams. That upstream pressure often lands on the management of PFAS in landfill leachate and how it is handled across the treatment and disposal chain.

This is not about drinking-water rules directly regulating leachate. The impact is indirect, but operationally real, because endpoint transparency tightens expectations upstream. Persistent chemicals like PFAS create long-term exposure pathways; 2026 marks the year when simply "passing them downstream" is no longer a viable strategy.

The ripple effect: Why landfill leachate PFAS treatment becomes an interface issue

The 2026 shift is not only about limit values; it is about transparency and comparability. The EU has communicated this change as a major step now in application. As PFAS is monitored and reported more consistently under the ‘PFAS Total’ and ‘Sum of PFAS’ parameters, expectations tighten at interfaces. In the EU, this is implemented using the ‘PFAS Total’ and ‘Sum of PFAS’ parameters.

Operationally, this pressure shows up at handoffs:

- Downstream partners become more data-driven (acceptance criteria, sampling scope, documentation requirements).

- Costs become less predictable (surcharges, testing frequency, and more conservative operating margins).

- Side streams carry more weight in acceptance decisions (spent media, concentrates, sludge, backwash and flush waters).

This is where landfill leachate PFAS treatment becomes an operational interface topic, not just a unit-process discussion. The question is not only what leaves as treated water, but what is handed off, under what conditions, and with what residual responsibility attached.

PFAS leachate treatment: Capture-only improves effluent, then the bottleneck moves

Adsorption and ion exchange can remove PFAS from water. Membranes can reject PFAS. The operational issue is what “removal” means at the total system level.

PFAS does not disappear. It changes streams.

A typical PFAS treatment train built around capture can deliver strong effluent performance while creating PFAS-rich residual streams:

- Spent GAC (Granular Activated Carbon) and spent ion exchange resin,

- Membrane concentrate,

- Sludge, backwash, and flush streams.

Once PFAS is concentrated, the downstream pathway becomes the constraint. That is why PFAS residual management increasingly determines operational stability and OPEX predictability.

Capture-only as a relocation strategy, and why liabilities persist

In system terms, capture-only is a relocation strategy: the effluent improves, but residual volumes and complexity rise at the same time. As a result, logistics and documentation workloads increase, including storage, transport scheduling, and chain-of-custody requirements. Operations also become more exposed to the stability of off-site routes, where capacity constraints, pricing volatility, and changing acceptance conditions can quickly become the limiting factor.

Relocation is an incomplete risk strategy: it can meet an effluent target while extending long-term operational and liability exposure through the residual chain. In a high-transparency environment, the residual stream management stops being a back-end detail. It becomes a central risk driver for the whole treatment system.

RO concentrate PFAS: The uptime constraint many sites did not plan for

Membranes are powerful, but the PFAS load lands in the concentrate stream. That is why RO (Reverse Osmosis) concentrate PFAS is increasingly treated as a practical bottleneck across the water sector.

Concentrate becomes the constraint when:

- Storage fills faster than disposal windows open,

- pricing changes faster than budgets can adapt,

- receiver conditions shift (sampling frequency, maximum PFAS loads, conditional acceptance).

At that point, plant stability is governed less by rejection performance and more by how reliably concentrate can move through a stable downstream pathway.

What resilient operators track: PFAS residual management, mass balance, and route stability

Effluent concentration tells what is in the water at a single point in time, while a mass balance shows where PFAS goes across the entire system, including side streams. A resilient operating picture typically combines a basic PFAS mass balance across effluent and residual streams with clear identification of the true limiting link, whether that is a unit process or the residual route.

It also relies on early warning indicators that signal route fragility, such as rising changeout frequency, concentrate accumulation, shifts in acceptance criteria, and a growing analytics burden. Ultimately, closing the residual constraint requires technological approaches that target PFAS at the molecular level, not simply transfer it into another form.

Conclusion: Fewer handoffs, smaller concentrates, and a shift toward PFAS destruction

If the residual chain is becoming the limiting factor, then fewer handoffs and smaller concentrate streams become the operational objective. Every handoff adds cost, friction, and uncertainty. Responsibility remains open as long as PFAS exists somewhere in the chain.

In practical terms, the goal is to break the PFAS chain, not just manage it, so downstream systems, communities, and ecosystems are not left carrying residual risk.

The strategic shift is becoming clear: away from capture-only toward on-site solutions that do not just separate PFAS, but actually destroy or mineralize it. The objective is not perfection at the effluent point, but a robust overall operation: less concentrate volume, more stable OPEX, and a shorter responsibility chain that ideally ends at the gate.

In this context, electrochemical PFAS destruction is increasingly discussed as one pathway aimed at the molecule itself rather than moving it into another stream.

Is your treatment train ready for the shift? Contact us to discuss your specific leachate stream and explore how an on-site destruction technology can close your residual risk loop.